Editor’s Note: This is the second part of a three-part essay on eel fishing in Arkansas from a work by Mark Spitzer titled: NATURE OF THE AMERICAN EEL: AN AQUATIC PHANTOM IN ARKANSAS.

By Mark Spitzer

We arrived at the dam on the Caddo River right before sunset, where Casey had caught sixty eels the week before. In Arkansas, yellow eels head upstream in gregarious gangs in mid-May. We were coming off a time of high activity. Hopefully, a few stragglers were still trying to get over the dam.

Casey set up his ladder at the base of it, and I ran three hundred feet of extension cords to an outlet in the picnic area. The idea was to see if they’d be more inclined to travel through the tube if it seemed like an alternative to the main flow providing passage beyond the obstruction. Plus, if the ladder worked, we’d catch some as well.

We sat down and waited for the sun to drop. A few fishermen were casting nearby, and a guy came over.

“Whatchya fishin’ for?” was the question. Turns out he was a biologist at the local Baptist college and had done his dissertation on silversides in Mexico. More importantly, he told us he’d seen a bunch of Anguilla rostrata (meaning “beaked serpent”) down past the first bend.

importantly, he told us he’d seen a bunch of Anguilla rostrata (meaning “beaked serpent”) down past the first bend.

But you have to watch out for reports like that, especially since eels are hardly seen in the light. Or, for that matter, they’re hardly ever seen in the dark. This guy, however, was a professional, so they might’ve been the real thing, or they might’ve been amphibians, like sirens or amphiumas. Still, they might’ve been hallucinations, or fiction, or nothing at all—or lampreys, which are also in these waters.

I’d recently seen the lamprey episode of River Monsters in which Jeremy Wade had spectacularized lampreys as “Vampires of the Deep” lurking in American waters. As usual, he had solved the crime, but what I found interesting is how those literal suckers had ascended the second hugest waterfall in the United States by somehow worming their way straight up the mossy rocks while thousands of tons of hydro-pressure crashed down from above. Jeremy had gone straight into the blasting spray, groped around, and pulled them out with his hands.

Looking at that dam on the Caddo River, I wondered if eels could do the same. I’d seen videos of elvers crawling straight up concrete surfaces, so I knew they could get past different types of barriers.

For eels, dams are both good and bad. They’re problematic in the sense that they block natural movement patterns and only a certain percentage manage to get through. They’re especially harmful when producing hydro-electricity, since a good amount of eels get ground up by turbines. On the other hand, dams help control the parasites eels can carry and spread to each other. The more dams there are in a system, the less parasites there are upstream. According to a 2011 US Fish and Wildlife report on the status of American eels, “dams and natural waterfalls, which likely preclude movement of intermediate hosts, have been shown to significantly reduce infections of eels.” And at this point in time, there’s a particularly powerful parasite making the rounds. In 1997 it invaded ten to twenty-nine percent of the swim bladders in the Chesapeake Bay population. By 2000, more than sixty percent of Hudson Bay eels had been infected. Data is still being collected.

Dams can also cause low oxygen levels and their construction can seriously diminish habitat availability. Along with that, the dredging that accompanies the development of dams and levees has been known to decrease distribution through access to prey. Dams also cause turbidity and suspended sediments that mess with eels during all stages of their evolution.

Other threats include overfishing, excessive harvesting of juveniles, and pathogens. Then there’s destruction from logging, and contaminants like heavy metals, dioxins, PCBs, and chlordane, which lower reproduction rates. Oil spills and other forms of pollution are also mentioned in various sources.

And the threats to water quality just keep on coming: irrigation, water removal projects, runoff from neighborhoods, roads, golf courses, tennis courts, etc. But the most serious threats are from changes in oceanic conditions, which can severely affect larval transport and recruitment. Since ocean currents and temperatures are driven by the jet streams, and since jet streams affect the Gulf Stream, and since the Gulf Stream is now in flux due to excessive carbon dioxide, the highly delicate migration patterns of American eels are at risk of being irreversibly altered. But it’s not just eels that could suffer from the changing climatic equations. Since they’re directly connected to so many species in the food chain, a shift in their balance could catastrophically impact ecosystems worldwide.

Sitting on the shore of the Caddo, Casey and I were waiting for eels to enter the ladder. We were also talking about the world record (9.25 pounds) and the oldest one ever reported (eighty-eight years old), and the fact that they grow larger in salt water and in the South.

When night fell, we checked out the barrel (still nothing), then headed down to the boat launch to do some electro-fishing. Casey had a big backpack with a motorcycle battery in it and a bunch of cords and buttons on the back. The thing probably weighed a hundred pounds. It was connected to two long-handled tools. One was an electric prong that attracted fish and zapped them into temporary catatonia when they come within range. The other was a net used to scoop them up.

Donning the cyborg contraption, Casey asked me to turn the main nob up to two hundred watts. Since he was wearing rubber waders, he was protected, but since I was wearing river shoes, I remained on the shore with another net, shining a spotlight into the water. If I stepped into the river while he was zapping, I’d get shocked.

Casey stepped in and started poking underneath the larger rocks. Sunfish started floating up, and then a ten-inch longnose gar. He shocked a bass, ran into a water snake, and kept on heading upstream. There were lots of crawfish (a staple of larger eels) and minnows too, but no eels to be seen.

Moving upriver in the dark, I was astonished by how many fish there were within just a few feet of us. You’d think they’d take off when they sensed us coming, but there were loads of species hiding out.

As the current increased, the boulders started getting larger. It was only a foot or two deep where Casey was wading, but he was encouraged by the size of the rocks.

“These are the perfect size,” he told me, and then we saw one flash in the light and flip on its side.

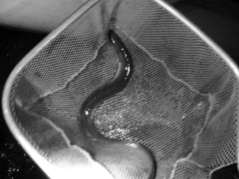

Casey scooped it up and handed it to me. It was about fourteen inches long and having a seizure. For a few seconds I thought it might go into cardiac arrest, but then it shook off its daze and tried to light off.

Casey tried some more but didn’t get squat. We figured that the brunt of eels from last week either managed to get over the dam, or they’d given up and had redistributed themselves throughout the stream.

Anyway, it was getting late, so we let that eel go and began packing up.

“Whatchy’all fishin’ for?” a woman’s voice asked, hardly audible above the rumble of her pickup truck, which sounded like a pack of Harleys.

“Eels,” Casey answered, sauntering over to say hello. She was idling in the parking lot with her two teenage daughters beside her in the cab. They were texting away and seemed annoyed at their mother for talking to random strangers.

“Eeeeels?” she replied. “I hate those things! Caught one last week five feet long! Thick around as my arm! Whatchy’all want with those disgusting things?”

“We’re collecting data,” Casey said, “for US Fish and Wildlife.”

I came over to her window and listened in. She was in her late thirties, had a few tattoos, and a camo-shirt with torn-off sleeves.

“It had nasty, little, beady eyes!” the woman continued. “How y’all fishin’ for ‘em?”

Casey explained the eel ladder and the zapper, but she just shook her head, acting like we didn’t know nothing.

“You gotta use chicken livers!” she said, then paused for a second. “Y’all ain’t fishin’ for catfish, are ya?”

“Nope,” Casey said, “we’re not interested in those right now.”

“You sure y’all ain’t fishin’ for catfish?” she shot back, giving him a sideways glance.

“No, no,” Casey laughed, “we just want eels.”

“Okay,” she nodded, then propped her elbow out her window. “Y’all see that spot over there, down by the boat launch? That’s the honey hole. I’m a redneck through and through, and I bring my daughters here at night, and we set up right next to the honey hole. I like river fish a whole lot more than from the store, and we catch loads of catfish in that spot! Y’all ain’t gonna tell no one about the honey hole, are ya?”

“No, no,” Casey assured her.

“Alright then. We catch a lot of cats in that spot. I once got one that was thirty-eight pounds. I clean ‘em myself. I shoot deer too, and clean ‘em as well. Anyways, last week we were trying to catch some cats, but all we kept catching was them damn eeeels! They just love chicken livers!”

At this point, Casey realized she was a valuable source of information.

“Would you be willing to fill out a survey?” he asked.

She looked at him with narrowed eyes.

“It’ll only take a few minutes,” Casey added, “and you can mail it in.”

She was not enthusiastic to respond, but Casey decided to go for it. “I’ll go get it,” he said, and shot off. I hadn’t said anything yet, so I figured I should try to get some info.

“What kind of hooks were you using?” I asked.

“They had a one slash zero on the package… and they were barbless.”

This didn’t seem right to me, but I didn’t challenge what she said. I mean, how can you make liver stay on a barbless hook? Typically, treble hooks are used for liver.

Casey came back with a survey designed for commercial fishermen and told her that it would really help him with his research. She accepted it, then hit the gas and drove away.

* * *

Mark Spitzer is the author of twenty books and an associate professor of creative writing at the University of Central Arkansas, where he is the Editor in Chief of the award-winning Toad Suck Review (toadsuckreview.org). His essay collection Season of the Gar (U of Arkansas Press, 2010) will soon be followed by a sequel entitled Return of the Gar (U of North Texas Press), and he is also working on a book called Beautifully Grotesque Fish of the American West for the University of Nebraska Press. He can be seen on the alligator gar episode of Animal Planet’s River Monsters series, or paddling through the tornado-littered sandtar soup of Lake Conway. For more info, go to sptzr.net.