As another running of the Kentucky Derby neared a week ago, national media attention was focused on the jockey aboard Santa Anita Derby winner Goldencents. The media didn’t focus on Kevin Krigger because he had won at Santa Anita or because he was riding one of the favorites in the race.

Reporters focused on him because he’s black.

Krigger, a native of St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, is 29. It has been 111 years since there was a winning black jockey in the Kentucky Derby. In fact, Krigger was the first black jockey to compete in a Kentucky Derby in years.

“All my life I grew up watching races and I knew there weren’t too many African-American jockeys,” Krigger said. “Being African-American is just a part of who I am.”

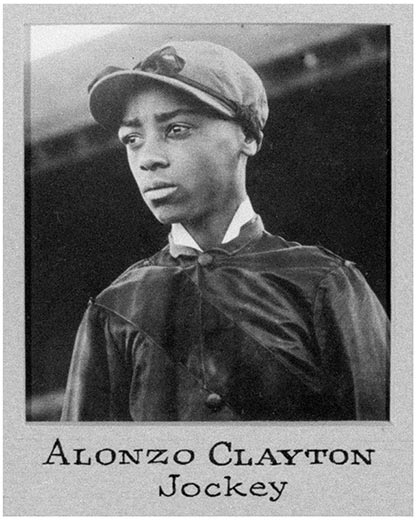

Goldencents finished a disappointing 17th out of 19 horses in the race. But the attention paid to Krigger brought to mind a former Arkansas resident who was once among the country’s top jockeys, Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton.

In 1892, at the age of just 15, Clayton became the youngest jockey to win a Kentucky Derby. Still, it’s safe to say that most Arkansans have never heard of him. That’s despite the fact that the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame inducted him last year in the posthumous category as part of its Class of 2012.

Clayton was born in Kansas City, Kansas, in 1876 and moved with his parents to North Little Rock when he was 10. There were nine children in the family, and finances were tight even though his father had steady work as a carpenter. Clayton worked as a hotel errand boy and as a shoeshine boy to earn extra income for his family.

In an 1896 story in the Thoroughbred Record, it was written that Clayton also had attended school as a boy and was considered “exceptionally bright.”

Clayton was only 12 years old when he left home to join his brother Albertus, a jockey who was riding at the time for the legendary E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin. Alonzo Clayton soon found work as an exercise rider for Baldwin’s stables. His first race as a jockey came in 1890 at Clifton, N.J. He had his first victory later that year.

Thoroughbred racing had become one of the top sports in America by that time, and it didn’t take long for those on the East Coast to recognize Clayton as a rising star. He won the Jerome Stakes aboard Picknicker and the Champagne Stakes aboard Azra at Morris Park in Westchester County, N.Y., in 1891.

On May 11, 1892, Clayton was aboard Azra in the Kentucky Derby. Azra came from behind in the stretch to win the race by a nose, and Clayton became one of only two 15-year-old jockeys to win America’s most famous race.

He would be in the money in the Kentucky Derby three more times in his career, finishing second in 1893, third in 1895 and second in 1897. Clayton’s best year was 1895 when he had 144 wins and finished in the money in almost 60 percent of his races. He won the Arkansas Derby that year at the Little Rock Jockey Club’s Clinton Park. In 1896, he became one of the few black jockeys ever to compete in the Preakness Stakes at Baltimore, and he finished third.

when he had 144 wins and finished in the money in almost 60 percent of his races. He won the Arkansas Derby that year at the Little Rock Jockey Club’s Clinton Park. In 1896, he became one of the few black jockeys ever to compete in the Preakness Stakes at Baltimore, and he finished third.

Other significant races won by Clayton were the Clark Stakes at Churchill Downs in 1892, the Travers Stakes at Saratoga in 1892, the Brooklyn Handicap and Futurity at Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn in 1894, the Kentucky Oaks at Churchill Downs in 1894 and 1895, the Cotton Stakes in Memphis in 1895, the Saratoga Stakes in 1895, the Latonia Derby in Cincinnati in 1897, the St. Louis Derby in 1897, the California Derby in San Francisco in 1898 and the Suburban Handicap in Brooklyn in 1898.

In an interview with the Chicago Daily Tribune, Clayton would call the Suburban Handicap “the greatest race I ever rode.”

Racing historian Ed Hotaling said Clayton “became one of the great riders of the New York circuit all through the 1890s, but he rode all over the country.”

“While spending most of his time on the road, Clayton, who never married, came back to North Little Rock regularly to visit family,” Cary Bradburn wrote in the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. “He bought his parents a farm in 1894 in what is now Sherwood and had the Queen Anne-style house (in North Little Rock) built in 1895. His celebrity status spawned a legend that erroneously linked him to another Queen Anne house, known today as the Baker House, a bed and breakfast at 109 West Fifth St. in North Little Rock. According to legend, Clayton, misidentified as Artemis E. Colburn, raced horses in England and came back to his hometown of Argenta (now North Little Rock) to build a grand house; however, he soon left the area.

“The reason for Clayton’s departure is not clear, but in a larger context racism did contribute. In the early 1900s, bigotry drove black jockeys out of the sport they had dominated in America since the mid-1600s. Most stable owners stopped hiring them when sanctions and even physical threats against black jockeys increased. Some went overseas, as Clayton may have done.”

Indeed, black jockeys once ruled the sport.

“These were the first great American athletes, white or black, and they were written out of the history books,” Hotaling toldThe Baltimore Sun. “The saddest part is that they weren’t and haven’t been brought back into the sport.”

Black jockeys won at least 15 of the first 28 runnings of the Kentucky Derby.

“Once economics – big money – came into racing, the black jockey was pushed out,” said Inez Chapel of the group African-Americans in Horse Racing. “And racism is still alive. There are black jockeys out there, but they do what they have to do. They claim to be Jamaican or something else. If you speak in an unknown tongue, then the color of your skin doesn’t bother people.”

As racing began to gain prominence following the Civil War, many horse owners used their former slaves as jockeys. Former slaves tended to gravitate toward the sport because they were comfortable working with horses. Jim Crow laws changed that. The majority of black jockeys were gone by 1910, though some continued to race in more dangerous steeplechase events.

“By 1910, they were all but gone,” Hotaling said.

Clayton and his family lived in what later would be known as the Engelberger House in North Little Rock from 1895-99. His earnings had enabled him to build a home that the Arkansas Gazette described in 1895 as the “finest house on the North Side.” The home at 2105 Maple St. was purchased by Swiss immigrant Joseph Engelberger in 1912. It was listed in 1990 on the National Register of Historic Places.

Bradburn wrote: “Written in pencil in the attic are the names of Clayton and eight brothers and sisters as well as ‘Mama and Papa Clayton’ and ‘1899’ and ‘Goodbye.’ On a baseboard to the right is a drawing of what appears to be a jockey, under which is written ‘Ragtime Jimmie,’ the meaning of which is unknown.”

Bradburn wrote: “Written in pencil in the attic are the names of Clayton and eight brothers and sisters as well as ‘Mama and Papa Clayton’ and ‘1899’ and ‘Goodbye.’ On a baseboard to the right is a drawing of what appears to be a jockey, under which is written ‘Ragtime Jimmie,’ the meaning of which is unknown.”

In April 1901, Alonzo Clayton was arrested at Aqueduct in New York for allegedly fixing a race. The charge later was dismissed, but his career was over for all practical purposes. He made short comeback attempts in Montana in 1902 and Memphis in 1904.

Clayton died in March 1917 in California of tuberculosis. He was only 41. He’s buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles.

In the Kentucky horse country at Lexington, they’re turning the former home site of Isaac Murphy, a black jockey who won the Kentucky Derby three times in the late 1800s, into a memorial art garden. Jimmy Winkfield, who like Murphy hailed from Lexington, was the last black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby in 1901 and 1902.

Prior to last week’s race, Thomas Tolliver, a board member of the Isaac Murphy Memorial Art Garden, told the Lexington Herald-Leader: “What excites me about Kevin Krigger being in the Derby and getting the attention he’s getting is that it gives recognition to all the black jockeys who have ridden in the race whose stories are so often overlooked. You can’t write the story about Kevin Krigger without mentioning it has been 111 years since there was a winning black jockey, and you have to talk about why they disappeared and the contributions they made.”

Maryjean Wall, a former racing writer who now teaches at the University of Kentucky, explained the change this way: “Purses got larger, and white jockeys and trainers started to kick black jockeys out. But no one has done a study of that. I don’t think it was a conscious act that way. I think it was all part of this prevailing fear and paranoia in white society at the time that spilled over into the horse racing world. Now we were legally segregated and we tried to make blacks disappear, and you can’t have them riding these super horses because then they are visible in society. They became grooms and exercise riders, but they’re not jockeys.”

At the website History.com, Christopher Klein describes the transition this way: “For centuries, Southern plantation owners put slaves to work in their stables. Slaves cared for and raced their masters’ horses. They served as riders, grooms and trainers and gained a keen horse sense from spending so much time in the stables. After emancipation, African-Americans continued to rule Southern race circuits while white immigrants from Ireland and England predominated in the North. …

“Then, suddenly, the rich African-American tradition at Churchill Downs ended. The rising tide of institutional racism that swept across Gilded Age America finally seeped into the world of horse racing. Jim Crow was on the ascent, and the U.S. Supreme Court itself blessed segregation in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Emboldened by the societal changes, resentful white jockeys at Northern raceways conspired to force blacks off the track, in some cases literally.

“During the 1900 racing season, white jockeys in New York warned trainers and owners not to mount any black riders if they expected to win. They carried out their threats by boxing in black jockeys and riding them into – and sometimes over – the rails. In a cruel irony, free sons of former slaves felt the sting of whips directed their ways during races. Race officials looked the other way. Owners realized that black riders had little chance of winning given the interference. Even Willie Simms, the only African-American jockey to win all three of the Triple Crown events, had to beg for a mount.”

Goldencents didn’t perform well in Louisville on Saturday, but the media attention Krigger received may have educated some on the great black jockeys of the past. Here in Arkansas, none were greater than Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton.