Editor’s Note: This is the first part of a three-part essay on eel fishing in Arkansas from a work by Mark Spitzer titled: NATURE OF THE AMERICAN EEL: AN AQUATIC PHANTOM IN ARKANSAS

By Mark Spitzer

When I showed up in the parking lot, Casey Cox was out by the dumpsters, looking a lot less gnome-like than when we sampled alligator gar a year ago. I’d seen this transition to the clean-cut look before with a few of our biology grad students at UCA, especially when they’re looking for jobs, like the internship Casey had recently scored. It was the perfect position for him, since he was studying American eels and the local US Fish and Wildlife office was responding to a push to list this creature as an endangered species.

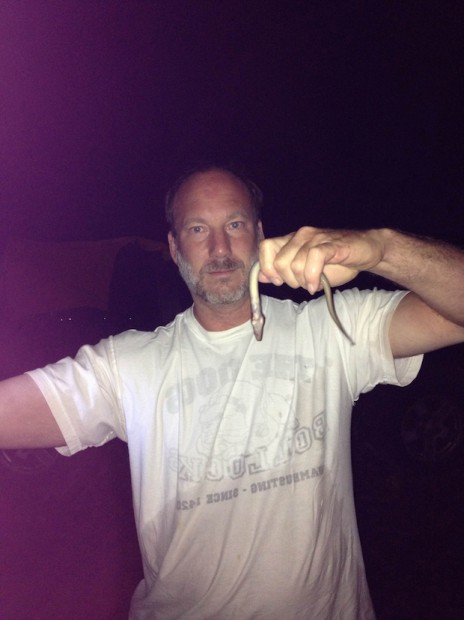

A blond, good-natured Navy vet in his late-twenties, Casey was catching eels all over the state. He was collecting data for his thesis, and working on an “eel ladder”―which is what these serpentine squigglers need to get beyond the dams that have been blocking migrations throughout their range.

American eels are usually associated with the Atlantic Coast and the river systems that enter the continent east of the Mississippi, but they also occur in the West. Swimming in through the Gulf of Mexico, they’re in every state along the Mississippi River, plus Texas and South Dakota. They used to exist in New Mexico, they’ve been recorded in Arizona, they were introduced in Utah and California, and they escaped from a facility in Colorado. They’re also in Nebraska, due to a railroad bridge collapsing in 1873, spilling a load of eels into the Elkhorn River.

Out of all the known fishes in the world (and yep, they’re actual fish with tiny, slimy scales), it’s speculated that this species—which exists from Greenland down to South America—has the widest known range of any fish in North America, sometimes traveling up to 10,000 miles. They’re born in the Sargasso Sea somewhere between the Bahamas and Bermuda, and being “catadromous,” they eventually head into freshwater, where they live for three to forty years until they’re sexually mature. That’s when they head en masse back to their secret spawning grounds (which no one has ever seen) to get it on and die.

“Howdy,” I greeted Casey.

We shook hands and he showed me a tub filled with nine American eels between eight and twelve inches long. Right above the water line there was a six-foot tube of PCV sewage pipe set at a forty-five-degree angle, heading up to a fifty-five gallon barrel. Casey was pumping water up to it, the water was flowing down, and there was a length of “substrate” going through it consisting of wire mesh and nylon netting material. Basically, this was an eel ladder.

An eel came up to the surface with its elongated spade-shaped head. It peeked into the opening, squirmed a few inches in, then backed out.

“They’re thinking about it,” Casey said, “but there’s probably too much light right now.”

It was early afternoon, and being nocturnal, eels are used to hunkering down during the day, hiding under rocks and logs. They do this throughout a third of the country and hardly anyone ever sees one—which is something I find staggering. Like tens of millions, I’ve spent most of my life amidst these fish, but have never caught one, or glimpsed one, or even heard of anyone catching one. It’s like they’re figments of our imaginations—or aquatic phantoms, appearing whenever they please.

do this throughout a third of the country and hardly anyone ever sees one—which is something I find staggering. Like tens of millions, I’ve spent most of my life amidst these fish, but have never caught one, or glimpsed one, or even heard of anyone catching one. It’s like they’re figments of our imaginations—or aquatic phantoms, appearing whenever they please.

But that’s the main thing about eels: they’ve been mystifying humans for centuries, thanks, in part, to philosophers like Aristotle, positing a bunch of bunk. He claimed they arose from the “entrails of the sea.” Then came Pliny, who wrote that they rubbed against rocks and the goo that came off turned into juveniles. Eventually, a medical student named Sigmund Freud took a more scientific look. He spent weeks dissecting the American eel’s European cousin in hopes of writing the seminal study on their testicles. He was unable to find them, so moved on to psychology. Go figure.

Another eel came undulating up and I commented that it must be a she to be so far upstream, since the males stay closer to salt and brackish water. Casey agreed and mentioned that sexual differentiation occurs between thirty and forty centimeters. Before that, they’re all “intersexual,” meaning they can go either way. According to a US Fish and Wildlife report from February 2007, gender is most likely “influenced by environmental factors, including eel densities.” When densities increase, so do males. When densities decline, so do the females. And the more lakes there are in an area, the more females there are as well, which tend to grow larger than the males—sometimes up to four feet long. Ultimately, they join up when they’re ready to breed, and the whole eely exodus heads out to sea.

An eel entered the tube and we cheered as it wiggled up, but then it stopped halfway. Another one entered. Then another. Something was driving them to follow the flow. Or maybe they just wanted to get out of the light. Whatever the case, they remained in there and refused to venture all the way up.

Casey said I could take one, and not too long after that, I came home with a bucket. My wife Robin met me at the front door and asked me what its name was. I dug through my mind for the most ludicrous, non-eely word I could think of and immediately replied, “Fire Hydrant.”

through my mind for the most ludicrous, non-eely word I could think of and immediately replied, “Fire Hydrant.”

She rolled her eyes as I dropped our new pet into an aquarium I’d set up in our mutual office. The observations had begun.

After being eggs and larvae, eels go through four more stages in their life cycles. Fire Hydrant was a “yellow eel,” and she definitely had a champagne sheen. Mostly, though, she was olivine-gray with a bright white belly.

The juveniles are referred to as “glass eels,” because they’re transparent. They enter this stage when they’re about six centimeters long, and then they metamorphose into “elvers.” This stage lasts three to twelve months, during which time they try to evade catfish and bass. Ultimately, the survivors become “silver eels” and assume a much more muddy color. Their wrap-around fin becomes even larger, and if you catch one big enough to eat, all you have to do is filet it. A commercial fisherman once gave me one, and it wasn’t fishy tasting at all. We grilled it with some olive oil and paprika, and the meat was white and sweet.

Fire Hydrant, however, had disappeared the morning after I brought her home through a gap the size of three dimes stacked on top of each other. When I pulled back the desk, I could see water splattered against the wall, and then her tail beside the baseboard. I grabbed her and she was still alive, so I put her back in, figuring eels must have lung-like organs—a trait Casey later confirmed was a necessary accessory for traveling from mudhole to mudhole when streams go dry.

This was a job for duct tape, so I sealed the gap, then threw in a minnow. I also tossed in a partial worm.

But the next day, Fire Hydrant was gone again. I’d read in James Prosek’s Eels: An Exploation from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Mysterious Fish (HarperCollins, 2010), that he tried to keep eels, but they were masters of escape that had even committed suicide by banging their heads against the glass.

I looked all over the room, and even in some adjacent rooms, but couldn’t find Fire Hydrant anywhere. Still, I figured I’d keep the aquarium going, since I intended to catch an eel myself.

A couple of times, working at that desk, I thought I heard the gravel shift, but I told myself I was just tripping out. I had sifted through that gravel earlier and hadn’t found any traces of the eel, but two days later (or nights, rather), there she was, hanging out in the alligator grass.

Unfortunately, Fire Hydrant only came out at night, and wasn’t letting me see her much. Some pet she turned out to be! What I was trying to observe was a creature that defied observation. No wonder Pliny and Aristotle got it wrong.

But as anyone can see on YouTube, there are plenty of eelcams to be accessed online. You can see American eels in various stages slithering through ladders, and you can see hundreds packing the streams while ballet music suggests some sort of semi-sexual, primeval dance.

Perhaps that’s what intrigued Freud—the way they swim together in spermy formation, eventually develop phallus-heads, then experience the ultimate ecstasy, recreating themselves through death. Perhaps that’s why their reputation has been interpreted through a mystical lens. But whatever the case, it was time for me to get out in the field and take a more (bio)logical look.

* * *

Mark Spitzer is the author of twenty books and an associate professor of creative writing at the University of Central Arkansas, where he is the Editor in Chief of the award-winning Toad Suck Review (toadsuckreview.org). His essay collection Season of the Gar (U of Arkansas Press, 2010) will soon be followed by a sequel entitled Return of the Gar (U of North Texas Press), and he is also working on a book called Beautifully Grotesque Fish of the American West for the University of Nebraska Press. He can be seen on the alligator gar episode of Animal Planet’s River Monsters series, or paddling through the tornado-littered sandtar soup of Lake Conway. For more info, go to sptzr.net.

Editor’s Note: Next week follow Mark and Casey as head out to the Caddo River to catch eels.