When Bennie Fuller is inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame on the evening of Feb. 28, no one will be happier than Little Rock’s Emogene Nutt, whose late husband Houston Nutt Sr. coached Fuller as a high school basketball player at the Arkansas School for the Deaf.

When Bennie Fuller is inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame on the evening of Feb. 28, no one will be happier than Little Rock’s Emogene Nutt, whose late husband Houston Nutt Sr. coached Fuller as a high school basketball player at the Arkansas School for the Deaf.

It was Emogene who once referred to Fuller as the “Wilt Chamberlain of the deaf.”

Fuller is the all-time leading scorer in Arkansas boys’ high school basketball history and still ranks fourth on the national scoring list. He scored 4,896 points at the School for the Deaf from 1968-71. In Arkansas, no one comes close to Fuller in the career points category. Jim Bryan of Valley Springs is second with 2,792 points from 1955-58, and Allan Pruett of Rector is third with 2,018 points from 1963-66.

Fuller ranks third nationally on the per-game scoring average list. He averaged 50.9 points per game during the 1970-71 season. In 1971, he scored 102 points (you read that correctly) in a game against Leola.

But this is not a story about Bennie Fuller. I already wrote that story a few months ago.

This is a story about Emogene and Houston Nutt Sr. and their years of service to this state. Houston Sr. mentored hundreds of young deaf students, and Emogene was like a second mother to all of them.

Their four sons are well known to sports fans in this state.

The two who were football coaches – Houston Dale and Danny – are off the sidelines these days, though Danny has just joined Kim Dameron’s staff at Eastern Illinois.

The two who are basketball coaches are still hard at it. Dickey is the head coach at Southeast Missouri State University. Dennis is the head coach at Ouachita Baptist University.

On the evening of Jan. 29 in Cape Girardeau, Dickey notched his 250th career win as a college head coach when SEMO defeated the University of Missouri-Kansas City. In 13 seasons as the head coach at Arkansas State University, Dickey compiled a 189-187 record. On the same night that Dickey got that 250th victory, son Lucas broke the all-time career assists record at SEMO.

“It’s a special feeling as a dad and as a coach to have a player reach a milestone,” Dickey said after the game. “I’m happy for Lucas, and he deserves a lot of credit. He’s one of the most unselfish guys on our team.”

Emogene stays busy this time of year watching her sons coach basketball and her grandchildren play sports. She has 13 grandchildren, including two sets of twins and one set of triplets. And she has been busier than normal since she’s writing a book about her late husband.

“I guess I knew one day I would write a book about Houston,” she says. “It’s more than being born to deaf parents and raised in a deaf environment where all of his siblings were either totally or partially deaf. It’s even more than having played for two legendary coaches. It’s about the American dream. Things in Houston’s life that could have been a detriment to some people were handled with ease. Houston set high goals for himself in athletics. His dream was to grow up and make life better for deaf people. In addition to this dream, he had an unbelievable passion for basketball. He pulled himself up by his own bootstraps. Because of Houston’s dedication and hard work, he earned a college education and lived out his dream of coaching basketball and working with the deaf.”

Houston Sr. and Emogene moved onto the School for the Deaf campus in 1956.

“When we came to the school, the language was not referred to as American Sign Language,” Emogene says. “It was just called sign language, and seeing it for the first time I was totally spellbound. I was intrigued, and I wanted to learn that language. As for deaf culture, it was never a topic of discussion, nor was it ever mentioned in any of my deaf-education classes. Today, deaf culture is all the talk. Everyone wants to know about it and who is part of it.”

She says conversation in the deaf community can be “very blunt, straightforward and to the point.”

Emogene hopes to use part of the book to explain the complexities of the deaf culture. One such complexity, she says, is that “being deaf doesn’t mean you are a part of the deaf culture. For example, people who lose their hearing from illnesses or deaf children who are born to hearing parents often haven’t been privileged to sign language or the knowledge that makes up the deaf culture. Most do acquire the language and culture later in life. However, their acceptance in deaf culture partially depends on their skill in the language.

“Then there are people like Houston Sr., who are born into deaf culture, inherit the language and take pride in it. If you’re not born into this culture, the next best way to learn about it is to live in the residential dormitory at a deaf school.”

When the Nutts arrived at the Little Rock school as newlyweds, most of the staff members were deaf people who once had been students. It was a learning experience for Emogene.

“The children are observing attitudes, prejudices, engaging in social behaviors and participating in games and sports, all of which are part of deaf culture,” she says. “The deaf children are submerged in this language and culture all of their school days, and it is passed down from generation to generation. I believe there will always be a deaf culture.”

Things, though, have changed drastically since 1956.

“We have come from a time when the deaf were embarrassed to be seen signing in public to a time when every public event has an interpreter,” Emogene says. “The deaf clubs, once necessary for social gatherings and to gain information, have been replaced by the Internet and all of the telephone technology.”

Houston Sr. died in April 2005 at age 74. At the time of his death, he and Emogene had been married for 49 years.

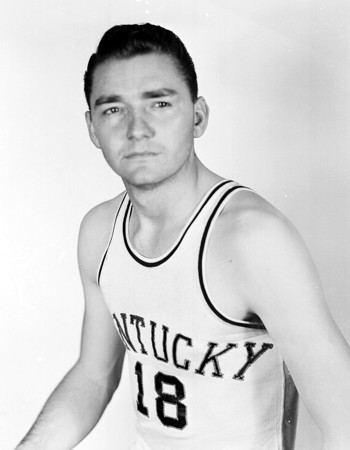

Houston Sr. graduated from Fordyce High School in 1951 and earned a basketball scholarship to play for Adolph Rupp at the University of  Kentucky. Rupp had been coaching at Kentucky since the fall of 1930 and would remain the head coach there until the spring of 1972, compiling an 876-190 record in the process. Rupp had learned about Houston Sr. because the head football coach at Kentucky just happened to be from Fordyce. You might have heard of that football coach. His name was Paul “Bear” Bryant.

Kentucky. Rupp had been coaching at Kentucky since the fall of 1930 and would remain the head coach there until the spring of 1972, compiling an 876-190 record in the process. Rupp had learned about Houston Sr. because the head football coach at Kentucky just happened to be from Fordyce. You might have heard of that football coach. His name was Paul “Bear” Bryant.

Houston Sr. hitchhiked from Fordyce to Lexington, Ky., to enroll in college. The Wildcats were the defending national champion. Kentucky went 29-3 during Nutt’s freshman season and made it to the NCAA Elite Eight.

In October 1951, three former Kentucky players were arrested for having taken bribes from gamblers to shave points in an NIT game against Loyola during the 1948-49 season. The Southeastern Conference voted to ban Kentucky from competing during the 1952-53 season due to the point-shaving scandal, and the NCAA advised nonconference teams not to schedule the Wildcats. The 1952-53 season was scrapped.

Houston Sr. enrolled at Little Rock Junior College with the idea of going back to Kentucky after a year. Instead, he wound up transferring to Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University) in 1953 to play for yet another legend, Henry Iba.

How many people could say they played for Rupp and Iba and were personal friends with Bryant?

Just one.

Rupp, Iba and Bryant were three of the most famous college coaches of all time. Houston Sr. had quite a network.

“While I was a student at Oklahoma A&M, a tall, thin, handsome guy came strolling through the library with a friend and just happened to sit down at my table,” Emogene remembers. “He got my attention and said, ‘Do you know me?’ My reply was, ‘No, I don’t know you.’

“In so many words, he explained he had played basketball for Adolph Rupp at Kentucky and was now playing for Coach Iba. I wasn’t impressed. I knew absolutely nothing about basketball. Furthermore, I wasn’t at all interested. After this introduction, I would occasionally see Houston on campus. He stood out because he was at least a head taller than most everyone else and had this huge smile and big, friendly wave. As time went on, I learned that Houston was definitely in the minority. He didn’t drink or smoke, never used bad language.”

Emogene was impressed.

During his senior year at Oklahoma A&M, Houston Sr. persuaded Emogene to attend a basketball game. After graduation, he had the opportunity to be a graduate assistant for Iba or play basketball for the Phillips 66 Oilers, an AAU powerhouse. He turned down both opportunities.

Houston Sr., you see, believed his calling was to work with deaf children.

Emogene went to Fordyce to meet Houston Sr.’s family and also visited the Arkansas School for the Deaf on that trip to Arkansas. Marriage soon followed along with a new life in Little Rock.

“Houston whisked me off my feet, and I landed at the Arkansas School for the Deaf,” Emogene says.

Bennie Fuller, who grew up near Hensley and learned to shoot a basketball into a hoop made from a bicycle wheel, and hundreds of other deaf children were the beneficiaries of the Nutts’ decision to spend their careers at the school.