Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a four-part series about retiring Arkansas Razorback emeritus athletic director Frank Broyles, whose last official day at the UA was June 30. Part three is available here.

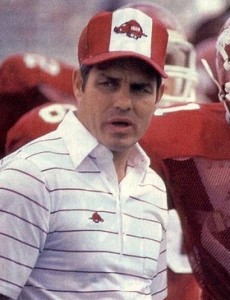

Ken Hatfield would not accede to Frank Broyles’ wishes to make staff changes at the end of the 1987 season, and he hired an agent and began negotiating for a new contract in 1988. Arkansas had begun the 1987 season expected to win the Southwest Conference title and was high in the preseason polls, but the Hogs finished 9-4 with losses to Miami, Texas, league champ Texas A&M and Georgia 20-17 in the Liberty Bowl.

Ken Hatfield would not accede to Frank Broyles’ wishes to make staff changes at the end of the 1987 season, and he hired an agent and began negotiating for a new contract in 1988. Arkansas had begun the 1987 season expected to win the Southwest Conference title and was high in the preseason polls, but the Hogs finished 9-4 with losses to Miami, Texas, league champ Texas A&M and Georgia 20-17 in the Liberty Bowl.

Fans fumed about the offense and the lack of passing that had cost the Texas game, and even starting quarterback Greg Thomas wanted to be trusted to throw more than he was allowed, so Hatfield opened it up somewhat against Georgia, only that game got away thanks to late interceptions. The Hogs lost on a last-second field goal to one of the SEC’s better teams.

However, it all came together for Hatfield and the Razorbacks over the next two seasons with back-to-back Southwest Conference championships, including a 23-22 win at College Station to highlight the ’89 season.

Broyles indirectly got some of his wished-for staff changes thanks to the success in 1988. Rice hired away defensive coordinator Fred Goldsmith. The year before, quarterback coach David Lee became head coach at UTEP. In 1989, Hatfield summoned offensive coordinator Jack Crowe from Danny Ford’s Clemson staff, and Arkansas traded the “flexbone” for a straight I formation that highlighted powerful running backs Hatfield had assembled in a better way than a full-house backfield. Arkansas set offensive records galore in 1989, and the defining moment was the 45-39 win over high-powered Houston and Heisman winner Andre Ware in Little Rock.

Hatfield won neither of his Cotton Bowl trips — the Hogs had just 42 yards of offense in losing 17-3 to UCLA and quarterback Troy Aikman, then put up record-setting yardage the next year against Tennessee but committed too many red-zone turnovers in a 31-27 loss.

Hatfield was ready to get away from Broyles before the UCLA Cotton Bowl and was set to take the Georgia job, but he wouldn’t be able to bring most of his assistants, as the story goes, so he withdrew. There was no such problem in mid-January 1990 when Clemson called. Danny Ford had gotten crossways with the school president and was fired. Hatfield, who still didn’t have a new contract but had found out that Broyles had just signed his new five-year deal, took the Clemson job over a phone call.

of his assistants, as the story goes, so he withdrew. There was no such problem in mid-January 1990 when Clemson called. Danny Ford had gotten crossways with the school president and was fired. Hatfield, who still didn’t have a new contract but had found out that Broyles had just signed his new five-year deal, took the Clemson job over a phone call.

Everybody on Hatfield’s staff left with the exception of Crowe, who Broyles hailed off the plane to take over and try to save the recruiting class.

Hatfield’s departure was probably the first inclination to the fan base that Broyles, the former coach, had begun to meddle too much in his successful coaches’ business, though there were hints of it with Eddie Sutton and his successor, Nolan Richardson.

Sutton, already having a tit-for-tat with Broyles on several items in 1985 after 11 winning seasons as basketball coach, was nearly about to bolt Arkansas for Auburn, where former UA president James Martin was working. Over a long phone call when the Hogs were in Salt Lake City for the NCAA Tournament, Sutton and Broyles seemed to work it all out and Sutton said he’d stay.

But on April Fool’s Day that year, it all changed. Kentucky had been turned down by several big names including Georgetown’s John Thompson and the Wildcats then turned to Sutton, who would draw the ire of Arkansas fans soon afterward by saying he “would crawl to Kentucky.” Later, Sutton would confess he aimed that comment solely at Broyles and Arkansas Gazette sports editor Orville Henry.

Henry would also pepper his paper with subtle attacks at Hatfield (and more toward his coaching staff) during the 1987 season, and Hatfield would later say it was then that he knew the writing was on the wall as well.

Such was the relationship that Broyles and Henry had for decades. What Broyles wanted the fans to know usually came out of the typewriter of Henry.

However, even that relationship would change, thanks to Nolan Richardson.

On Bob Knight’s advice, Broyles was set to hire Illinois State’s Bob Donewald as Sutton’s successor, but something about Tulsa coach Nolan Richardson’s personality captured Broyles’ attention. Then, Villanova’s Rollie Massimino, fresh off a surprise national championship, convinced Broyles he was interested, though it was only to get a raise out of his school. So, Broyles turned the program over the Richardson, who would be the first African-American coach at Arkansas as well as in either of the two major sports in the Southwest Conference and whose style was a complete departure from Sutton’s game.

Richardson’s personality captured Broyles’ attention. Then, Villanova’s Rollie Massimino, fresh off a surprise national championship, convinced Broyles he was interested, though it was only to get a raise out of his school. So, Broyles turned the program over the Richardson, who would be the first African-American coach at Arkansas as well as in either of the two major sports in the Southwest Conference and whose style was a complete departure from Sutton’s game.

It would take time and recruiting to make that new system work, as Broyles should have known from his own coaching experience, but he almost didn’t give Richardson two years. Once again, powerful boosters who didn’t understand were getting Broyles’ ear over the required patience to let the building continue. There are those who are convinced Broyles would have fired Richardson after year two had he not beaten Arkansas State in an NIT game in Fayetteville in March 1987, though both then-chancellor Dan Ferritor and then-UA president Ray Thornton insist they would not have allowed it. Orville Henry, as well, had been convinced by then that Richardson knew what he was doing.

Certainly, we know the rest of the story over the next nine seasons, as Richardson built a basketball powerhouse that, by the mid-1990s, was alongside Duke, North Carolina, Kansas and Kentucky in terms of winning. Coincidentally, Arkansas defeated Duke 76-72 for the 1994 national title, and Richardson reached the Final Four three times in a six-year period. The success required a new arena seating 19,200 and half-paid-for by Bud Walton. TV microphones picked up Broyles, at a post-championship celebration at Bud Walton Arena, telling Richardson, “You know I always believed in you.”

And, yes, that would change as well.

But, with Richardson winning big, Broyles didn’t have to worry about basketball at this time. Restoring football’s image was his first and pretty much only priority in the 1990s.

The Jack Crowe experiment failed, despite the best early efforts of Broyles and Henry to convince the masses that Crowe was an offensive genius not unlike the other redhead, Broyles, was when he took the Arkansas job in 1958. Arkansas went from a 10-win SWC champion in 1989 under Hatfield to nearly the basement in 1990 in a 3-8 year, salvaged only by a comeback win over SMU, which was just two years from restarting its program from the NCAA death penalty.

Surprisingly (surely to Broyles and his aides, if not everyone else), Crowe coached Arkansas into SWC contention briefly in 1991 and the 6-5 Hogs earned an Independence Bowl bid, where it gamely hung with talented Georgia despite starting a walk-on at quarterback.

But Crowe, who was making sure Broyles knew every aspect of game plans and the like, wasn’t even given a second game in 1992 when the Razorbacks opened at home before just 37,000 fans and lost 10-3 to Division 1-AA The Citadel. Broyles elevated exuberant, technically sound defensive coordinator Joe Kines to the head coaching job, and Arkansas upset No. 4 Tennessee and stomped South Carolina and LSU while somehow losing to Memphis and SMU. Kines had smartly summoned his friend, the out-of-work Danny Ford, to serve as a consultant in midseason and especially help with a punting game that had suffered the ignominy of four blocked punts against Memphis.

Then Ford hung around to be convinced by Broyles to take over the program. And even though Ford in his third year guided Arkansas to a stunning SEC West championship, he too would be a victim of Broyles’ meddling by his fifth season when the AD ordered him to hire two new coordinators after a 4-7 fourth season. One would have to look far and wide to find any successful college program that had hired two new offensive and defensive coordinators in such fashion, forced from within. Usually, it’s just a one-year reprieve for a beleaguered coach. Naturally, Arkansas didn’t begin to jell in 1997 until the last three games of the season. Ford, if he was really ever that enthused about the job, was done.

But Ford set a great table for his successor with SEC quality athletes. Houston Nutt took those players to 17 wins in two years and a share of the SEC West title in his first. Orville Henry, if he were alive, would tell you Nutt was not Broyles’ first choice as head coach and that his first choice was set to take job.

However, by 1997, with the way he’d handled his previous coaches and the two most recent searches, Broyles’ power with the big-players and the Board of Trustees had begun to wane. Then-UA chancellor John White feigned a support of Broyles and the athletic department outwardly, but inwardly he was determined to change the order of importance at Arkansas.

However, by 1997, with the way he’d handled his previous coaches and the two most recent searches, Broyles’ power with the big-players and the Board of Trustees had begun to wane. Then-UA chancellor John White feigned a support of Broyles and the athletic department outwardly, but inwardly he was determined to change the order of importance at Arkansas.

White’s decision to have a selection committee to choose the next football coach, rather than relying solely on the athletic director, is another decision at the UA that will be debated for decades.

Orville Henry, by midseason 1997, had already set the wheels in motion with the fan base for the hiring of Tommy Tuberville, who had turned Ole Miss around despite NCAA scholarship reductions due to recruiting sanctions against the previous Rebels’ staff. Tuberville wasn’t about to publicly interview for any job; Nutt, coaching at fledgling D-I program Boise State and a native son wanting the Hog job, was all but paraded in by his supporters. Tuberville met secretly with some of the search committee in New York, but ultimately he wouldn’t get the unanimous vote that White required.

Nutt did.

And early on, Nutt succeeded in restoring the excitement to Razorback football and competing against the SEC’s best.

With football apparently back, Broyles could turn his attention to basketball, which was falling off. Richardson had lost his edge and didn’t seem to take recruiting as seriously as he did when he built the program to Final Four level. White wasn’t keen on Richardson’s academic record, with few if any players obtaining degrees. From all appearances, and from testimony gathered in a suit Richardson would later bring on the UA for his firing, they ganged up on him.

Again, those big-moneyed boosters also turned on coach as well, even before his firing in 2002. Broyles wanted to dump Richardson in 2000, but the coach’s squad surprised by winning Arkansas’ only SEC Tournament title and earning an NCAA bid. When fortunes again took a downturn in 2002, Richardson became aware of the machinations behind the scenes and told reporters that if the UA wanted him out, “they can pay me my money.” He’d made similar statements in the past, but back then he was winning. This time it got all the attention. White and Broyles fired him.

Encouraged by Little Rock civil rights lawyer John Walker, Richardson sued for wrongful termination. He didn’t win, but more light shined down on the operations behind-the-scenes at Fayetteville and attitudes of some of the program’s biggest supporters.

Broyles wanted to hire Bill Self, then at Illinois and a young, successful white coach, as Richardson’s replacement, but the possibility of the discrimination suit scared White. Instead, Arkansas went with one-year wonder Stan Heath, a black coach from Kent State. Heath won the press conference but struggled early on the court. He hit his stride in years four and five with back-to-back NCAA Tournaments. And still, Broyles sacked him, but not before he again ordered Heath to shake up his coaching staff after year three.

Broyles hired Dana Altman from Creighton in 2007 and then left town for his annual pilgrimage to Augusta National Golf Club, and Altman backed out of the job the next day. At that point, White was through with Broyles doing the hiring and brought in a search firm to provide him some names; John Pelphrey’s made the cut, even though he had had marginal success at South Alabama. Still Pelphrey started strongly by coaching Heath’s leftovers to an NCAA Tournament win in 2008. But Arkansas hasn’t been back since, even after three years under Mike Anderson, at one time Richardson’s right-hand man and Jeff Long’s choice for basketball coach after dismissing Pelphrey.

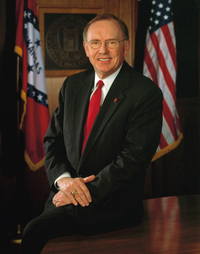

Broyles’ time in the 2000s was full of head-scratching moves and statements, such as the ones that ultimately led to the end of Houston Nutt’s tenure at Arkansas and, ultimately, Broyles’ end as athletic director. At a Dallas meeting of Razorback supporters in 2007, Broyles sought to defend his coach, Nutt, and to explain how he knew offensive coordinator Gus Malzahn’s offense wouldn’t work in the SEC and in doing so said, “I’ve been a coach for 60 years …”

Perhaps that was the biggest problem for Broyles in damaging his overall legacy as athletic director at Arkansas: He actually was a coach for 28 years and was entrusted solely with the athletic director job for 32, but apparently he still thought of himself as the coach the entire time, as some former Razorback head coaches could attest.

Should he have stepped aside, say, at the end of 1999, at age 75, with football in good hands and basketball still an NCAA Tournament factor? Would the UA have had a more peaceful next decade with folks in charge who had learned and worked under Broyles? Would we have seen such acrimony in the early 2000s from the former basketball coach, or such polarization of the football fan base in 2006 had Broyles moved on to other interests? Or were we blessed that Broyles had such an interest in Arkansas, from that first moment he saw the Arkansas people in the stands supporting their Hogs in 1948, that he simply could not step away until he had no choice, but giving every ounce of what he had?

Should he have stepped aside, say, at the end of 1999, at age 75, with football in good hands and basketball still an NCAA Tournament factor? Would the UA have had a more peaceful next decade with folks in charge who had learned and worked under Broyles? Would we have seen such acrimony in the early 2000s from the former basketball coach, or such polarization of the football fan base in 2006 had Broyles moved on to other interests? Or were we blessed that Broyles had such an interest in Arkansas, from that first moment he saw the Arkansas people in the stands supporting their Hogs in 1948, that he simply could not step away until he had no choice, but giving every ounce of what he had?

As a builder of an athletic program that has succeeded despite a small population base and a limited amount of funds, Broyles still must be viewed — at least early in his tenure — as one of the most successful athletic directors in college sports history.

As a football coach, he won more than 70 percent of his games at a school that, prior to his arrival, was mostly mediocre. Again, he overcame a lack of resources at his disposal to contend with the best, particularly from 1959-71.

In both roles, as AD and coach, he astutely was ahead of the game. His offenses in the late 1960s were running “counter-trey” and the like before the NFL’s Washington Redskins made it famous starting in 1982. He always had an eye on the up-and-coming coaches and got the best ones on his staff. He saw the importance of TV in the college game and befriended the men in that profession, resulting in success both personal for Broyles and for the Hogs. He saw the distant future of college football and assured Arkansas’ place in it by maneuvering the Hogs into the Southeastern Conference in 1990, on the front end of conference realignment.

He lost his first wife, Barbara, to Alzheimer’s, and has dedicated the rest of his life to bringing attention to that debilitating disease while raising funds for treatment and a possible cure.

As a man, Broyles has been ever gracious, ever giving of his time. To the Razorback fan, to the sports reporter and to just anyone on the street, he has been a true gentleman. That should be the most important legacy he leaves behind.