When Arkansas Travelers play ball at home in North Little Rock, baseball fans will head to Dickey-Stephens Park to enjoy games in one of the finest facilities in minor league baseball.

For those of us who cut our teeth at Ray Winder Field, it’s hard to believe it has already been more than six years since the Travelers hosted their first game at Dickey-Stephens on April 12, 2007.

The team’s staff has done a remarkable job keeping the complex looking new. Most Arkansans – at least those of a certain age – know of famed businessmen Jack and Witt Stephens. But fewer can identify the other two men for whom the park is named – former professional players Bill and George “Skeeter” Dickey.

Warren Stephens, the youngest son of the late Jack Stephens, donated the land along the Arkansas River for the stadium. During a groundbreaking ceremony in late 2005, he announced the park’s new name.

“My father and uncle loved the game of baseball and cherished their relationship with the Dickey family,” he said that day. “There are four good men smiling about this project and being able to keep baseball alive and well in central Arkansas. There was something pure about their love of the game and the relationship they shared. I knew what we wanted to call this park before there was any certainty we would be able to get it done.”

The Dickey brothers had worked for Witt and Jack Stephens at Stephens Inc. after their baseball careers ended.

Jack Stephens had far more sports involvement through the years than his older brother. Witt preferred talking politics. He also loved spending weekends on his family farm at Prattsville in Grant County. Jack, meanwhile, was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 2000. He became only the fourth chairman of the Augusta National Golf Club at Augusta, Ga., in 1991 and served in that role until 1998.

Jack Stephens had become a member at Augusta in 1962 and joined the executive committee in 1975. In November 1999, he made a $5 million gift to the First Tee, a national youth golf organization. He also gave $20.4 million to the University of Arkansas at Little Rock to build the Stephens Arena, the university’s on-campus basketball facility, which is among the finest arenas of its size in the country.

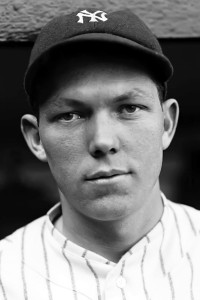

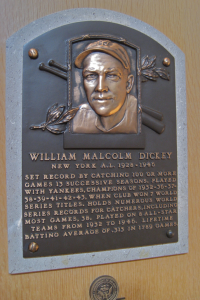

As for Bill Dickey, it’s a shame that more Arkansans don’t know his story. With all due respect to Brooks Robinson, Bill Dickey just might be the best baseball player to ever come from Arkansas. He was a member of the inaugural class of the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1959. The other members of that class were Lonoke native and famed New York Giants football player and coach Jim Lee Howell, Hendrix College playing and coaching legend Ivan Grove, women’s basketball star Hazel Walker and University of Arkansas football All-American Wear Schoonover.

Some baseball historians consider Bill Dickey the best catcher in the game’s history. Sportswriter Dan Daniel once said, “Bill Dickey isn’t just a catcher. He’s a ballclub.”

Dickey wasn’t born in Arkansas, but he always considered himself an Arkansan. He was born near the Arkansas line in north Louisiana at Bastrop. When he was 3 years old, his family moved to Kensett in White County, the community that produced another nationally famous Arkansan, Congressman Wilbur Mills. The Dickey family moved to Little Rock when Bill was 15.

One of our state’s greatest resources is the online Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture at www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Bob Razer of the Butler Center in Little Rock is among the state’s finest baseball historians. We’ll let him pick up the story. This is from his Dickey entry on that website: “Bill Dickey played for Little Rock College, a Catholic college, in 1925 and for a semipro team in Hot Springs. A scout for the St. Louis Cardinals was sent to Hot Springs to sign the young catcher, but the scout’s car had a flat tire. The delay allowed Lena Blackburne, manager of the Little Rock Travelers, to sign Dickey before the scout arrived.

“This was an era when any team – not just major league teams – could sign players to contracts. Dickey split the 1926 season between the Class C Muskogee Athletics in the Western Association and the Class A Southern Association’s Little Rock Travelers. In 1927, the Travelers lent the catcher to the Jackson Senators, a Mississippi team in the Class D Cotton States League.

“Because the Little Rock club had a working agreement with the White Sox, most major league teams assumed Dickey had signed a contract that gave the White Sox the option of buying it. Such an arrangement was common during much of baseball’s history. But Dickey had not signed such a deal, and Chicago failed to press any advantage it might have had with the Travelers. A New York Yankees scout was not so hesitant. After watching Dickey play, the scout urged his bosses to buy Dickey’s contract, saying, ‘I will quit scouting if this boy does not make good.’”

“Because the Little Rock club had a working agreement with the White Sox, most major league teams assumed Dickey had signed a contract that gave the White Sox the option of buying it. Such an arrangement was common during much of baseball’s history. But Dickey had not signed such a deal, and Chicago failed to press any advantage it might have had with the Travelers. A New York Yankees scout was not so hesitant. After watching Dickey play, the scout urged his bosses to buy Dickey’s contract, saying, ‘I will quit scouting if this boy does not make good.’”

As it turned out, the scout had nothing to worry about.

Dickey was assigned by the Yankees to the Travelers for the 1928 season, but he was moved to New York later in the season. He became the Yankees’ regular catcher in 1929 and batted .324. His longevity from that point forward was amazing. Dickey played for the Yankees until 1946. He was an All-Star selection in 1933, ’34, ’36, ’37, ’38, ’39, ’40, ’41, ’42, ’43 and ’46.

Dickey hit more than 20 home runs with more than 100 RBI in four consecutive seasons from 1936-39. His 1936 batting average of .362 was the highest single-season average ever recorded by a catcher until Mike Piazza of the Los Angeles Dodgers tied the record in 1997 and Joe Mauer of the Minnesota Twins broke it in 2009 by hitting .365.

Dickey’s lifetime batting average was .313. He struck out just 16 times in 1936.

“While Dickey excelled at two of the skills desired in a catcher – durability and hitting – he was equally known for his defense, throwing arm and the art of knowing how to pitch batters to get them out,” Razer wrote. “In 1931, he became the first catcher in history to go an entire season with no passed balls. He was also one of the first catchers to adopt a one-handed catching technique, a technique more difficult in Dickey’s day due to the smaller, less flexible catcher’s mitts in use then.”

Dickey’s best friend on the Yankees was Lou Gehrig. In fact, Dickey was the only Yankee teammate to be invited to Gehrig’s wedding and the first Yankee who Gehrig told of the disease that would end his life. Dickey played himself in the movie about Gehrig, “Pride of the Yankees,” which starred Gary Cooper.

Dickey’s best friend on the Yankees was Lou Gehrig. In fact, Dickey was the only Yankee teammate to be invited to Gehrig’s wedding and the first Yankee who Gehrig told of the disease that would end his life. Dickey played himself in the movie about Gehrig, “Pride of the Yankees,” which starred Gary Cooper.

Dickey served in the Navy during World War II, missing the 1944-45 seasons. In 1946, he was named the Yankee manager after Joe McCarthy was fired. In 1947, Dickey came home to Little Rock to manage the Travelers. He returned to the Yankees in 1949 as a coach under Casey Stengel and stayed with Stengel through the 1957 season.

Bill Dickey was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1954.

Younger brother “Skeeter” Dickey played for the Boston Red Sox in 1935-36 as a backup catcher. He also was a backup catcher for the Chicago White Sox in 1941-42 and 1946-47. His best season was 1947, when he appeared in 83 games while hitting .223 with one home run, six doubles and 27 RBI. He had a career average of .206 in six major league seasons.

By the way, the Babe Ruth field at the Junior Deputy complex in Little Rock also is named for the Dickey brothers. But it’s Dickey-Stephens Park that will most keep the memory alive – that and late-night cable showings of “Pride of the Yankees.”